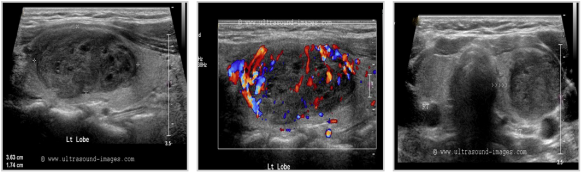

This post involves a personal experience from a free lance writer who asked me whether we (EM or primary care docs) should/can be doing bedside ultrasound for an assessment of the thyroid when we feel something wrong – even if its for the sole purpose of expediting care and biopsy, or alleviating concerns with a negative study. It was a valid question, and she wrote about her experience below. The thyroid is not a difficult gland to find, nor is it a technically difficult ultrasound to perform – although not a current use for bedside ultrasound, it may start to be given the ease to which nodules can be seen: (for pictures of normal thyroid and abnormal thyroid nodules, see the end of the post – the pics are not her thyroid)

Point-of-Care Ultrasounds: Can They be Used for Thyroid Nodules?

At a regular physical exam, my doctor discovered a small lump in my neck. She said it was on my thyroid, and referred me to an endocrinologist for further evaluation. At only 19 years old, I was scared and extremely uneducated in regards to thyroid health and diagnoses. My endocrinologist ordered a radiology ultrasound to be done at a later time where I had the technician hovering over me. After the doctor declared I had two nodules, I was scheduled to go back yet again for an ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) to help rule out cancer. This persistent waiting from one appointment to another for small amounts of information were frustrating, and I wondered why my own doctor couldn’t just do the initial ultrasound to visualize the nodules, streamlining the process and expediting my work up.

The day finally arrived for the FNA, and the scene couldn’t be more uncomfortable—and comical at the same time. As the technician tried to gain an image of the right spots with the large wand, the endocrinologist struggled to bypass the size of it in order to gain the samples he needed. On top of that, it was nearly four months from the time of my original physical exam before I found out I had benign nodules. I was told I would need to follow up with a radiology ultrasound every few years.

Point-of-care (POC) ultrasounds, units that are small and possibly hand-held that are increasing in popularity among physicians and emergency doctors, can used by primary care doctors with their assessment. Not only are they portable, but they are easier and more comfortable to use for all parties involved. While not widely publicized or used for thyroid nodules yet, there is potential that POC ultrasounds could aid in diagnosis and follow-up for related patients.

Defining Thyroid Nodules

Thyroid nodules are areas of abnormal cell growths within the thyroid gland. Depending on their size, nodules may form a visible mass in the neck. Some can also cause a goiter, or enlarged thyroid gland. The majority of thyroid nodules are not cancerous. However, an ultrasound and FNA can rule this out. These nodules may go undetected for years. Others can coexist with other related issues, such as hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. Thyroid nodules can also become painful to the touch and when you swallow.

Unless you can feel a lump in your thyroid gland, these types of nodules are first detected through a physical exam of the neck. Conventional radiology ultrasounds are currently used as a follow-up to locate the nodules and rule out any potential problems.

Role of POC Ultrasounds

On a larger scale, the increased use of POC ultrasounds can help the health of patients. It can even help save lives: although rare, thyroid cancer can be deadly if not caught early. Most cases of thyroid nodules and masses occur in older patients, some of whom may not be able to make it to radiology offices for a traditional ultrasound. By employing the use of a POC ultrasound, a physician can quicken the diagnosis and make the process more comfortable for patients. The fact is that once patients leave their primary care physicians’ offices, it is up to them to follow up on referrals to ultrasound appointments. Having a POC device handy ensures that a patient won’t miss these crucial diagnoses.

Having an ultrasound for thyroid nodules is easier with POC ultrasounds. Since the area of investigation is small, this approach makes the most sense when considering comfort for both doctor and patient.

Another benefit is the cost. POC ultrasounds cost providers less money, and it may be more affordable to patients. With the rising costs of healthcare, more and more patients are missing out on critical exams. By making thyroid scans more affordable, patients may be less likely to skip out on their appointments. The downside is that POC ultrasounds are not used for thyroid nodules yet. By pushing for their use in all areas of healthcare, POC may ease the ultrasound experience and even save lives.

Resources

- Thyroid Ultrasound. (2013, July 12). Retrieved from http://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info.cfm?pg=us-thyroid

- Point-of-Care Ultrasound: How to Demonstrate Proficiency and Quality – Head and Neck Surgeons Tackle the Challenges of Reimbursement Through Accreditation. (2014, January 23). Retrieved from http://www.aium.org/soundWaves/article.aspx?aId=713&iId=20140123

- What Are Thyroid Nodules? (2012, June 4). Retrieved from http://www.thyroid.org/what-are-thyroid-nodules/

Author Bio: Kristeen Cherney is a freelance health and lifestyle writer who also has a certificate in nutrition. Her work has been published on numerous health-related websites.

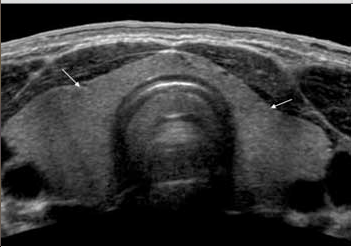

Pics from aium.org – NORMAL ADULT THYROID

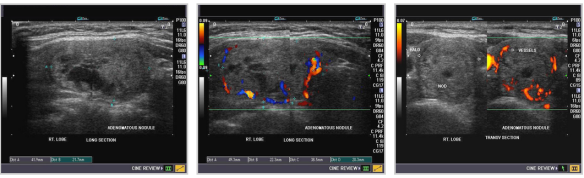

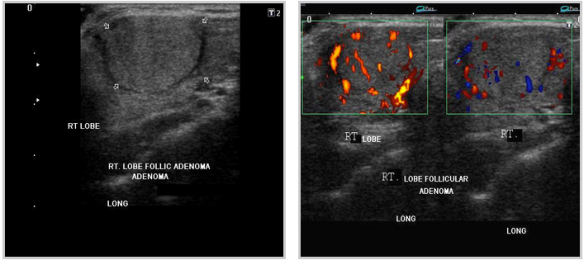

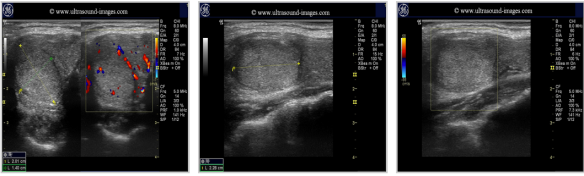

Pics form ultrasound-images.com :

ADENOMAS